Graz

1945–2003

After the Second World War, Graz was first occupied by Russian troops and finally part of the British occupation zone. The city’s population faced the ruins of war, denazification processes and the challenges of reconstruction. In the decades that followed, the public had to deal with the National Socialist past. Since the 1980s, this has been demanded with vehemence within the framework of art projects.

The path from the “City of the Popular Uprising” to the “City of Human Rights” in 2001 was not straightforward and cannot be considered completed down to the present day. Socio-political issues such as equal rights for women, the rights of homosexuals, dealing with cultural diversity in the city and tolerance have characterised the period from 1945 to this day. Urban planning, housing and transport are also important issues. 2003 marked a highlight in recent history: Graz was appointed European Capital of Culture.

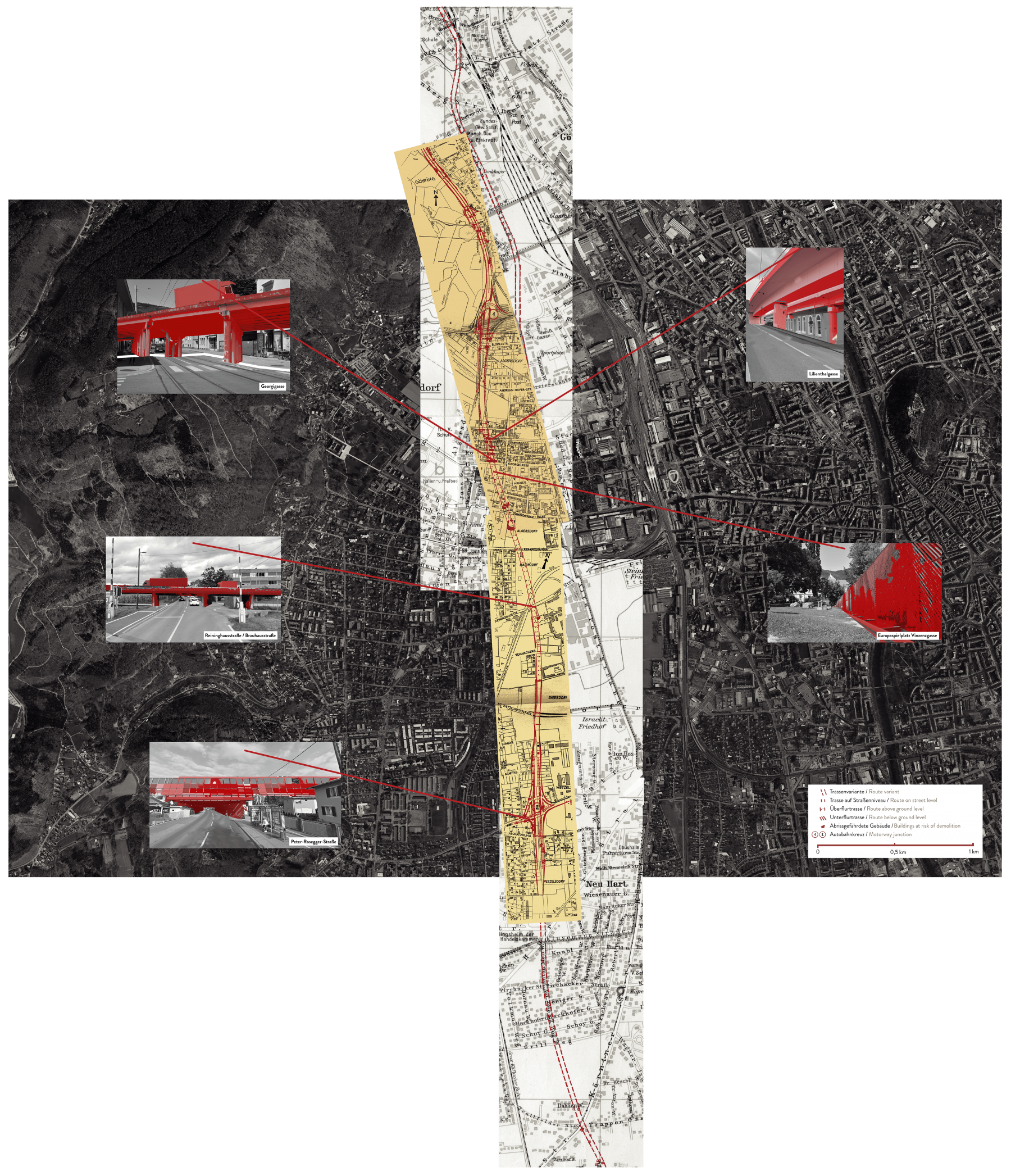

The Car-friendly Murvorstadt

A motorway across the Mur River, across a residential area or through the Plabutsch? As from the 1950s, the explosive increase of car traffic presented Graz in particular with big challenges. What came in addition was the traffic generated by the foreign workers from Yugoslavia streaming to the north. In 1970, the Municipal Council under social democratic Mayor Gustav Scherbaum resolved to route the highway as an underfloor route through the working-class residential areas in the west. A citizens’ initiative was formed and the city motorway project was prevented. As an alternative, the Plabutsch Tunnel was opened in 1987.

After Hans Haacke veiled the Marian Column at the Eisernes Tor (Iron Gate) with a sheathing reminding of the National Socialist demonstration in 1938, it was set on fire by right-wing extremists.

“Guilt and Innocence”

The (missing) reappraisal of the National Socialist past in Austria was also criticized by artists from the 1980s at the latest. As part of the steirischer herbst festival 1988, initialized by the art historian Werner Fenz, the artist Hans Haacke created a reconstruction of the obelisk with which the National Socialists had encased the Marian column at Eisernes Tor in 1938. At that time, the victory symbol was intended as an acknowledgement for the “City of the Popular Uprising”. With his memorial, Haacke drew attention to the crimes of the Nazi era. Right-wing extremists set it on fire. The general public responded immediately with protests in front of the burnt down obelisk.

Coming, Staying, Moving On: Migration as Permanent Political Challenge

Migration has shaped the history of Graz since it was first settled. After the end of the Second World War, Graz was a stopover for many Holocaust survivors on their way to the USA or Palestine. Thousands of former forced labourers, prisoners of war and “Volksdeutsche” (Ethnic Germans), as the National Socialists called them, who fled from formerly occupied countries, were accommodated in makeshift homes.

From 1948 Jews fled from the Soviet Union to Graz to escape Stalinist purges, and from 1956, political refugees fled from Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland. More than 90,000 people fled from former Yugoslavia to Austria and Graz due to the wars in the 1990s.

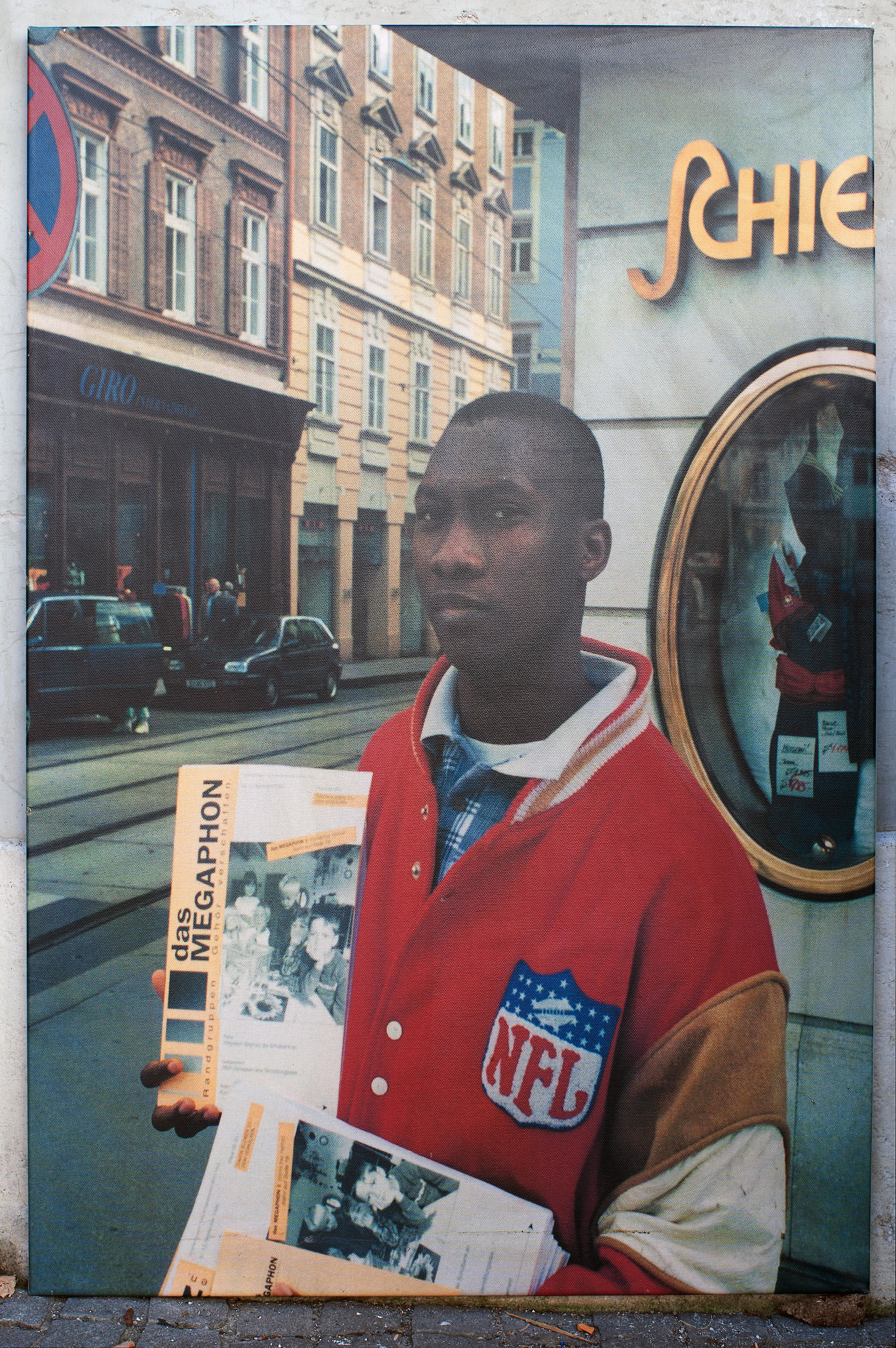

Migration is still a challenge for municipal politics and civil society today, most recently triggered by the Syrian Civil War. In 1995, “the Migrants Advisory Council” was established by the Graz Municipal Council as a stakeholder and advice centre.

Border after 1945 |

|

Border 2016 |

|

Migration 1945–1955 |

|

Migration 1956–1982 |

|

Jewish migration after 1945 |

The Project of the City

It was not until after the end of World War II that the civic project was continued under Mayor Eduard Speck. Its most important task was the fight against starvation, frost and housing shortage in the city administrated by British forces.

After the departure of the British occupying power in 1955, the civic project was understood as a top-down municipal policy. From the 1970s, however, the Grazers increasingly asserted their right to co-determination and co-creation in the form of civil society associations.

Similar to the civic principle of the Middle Ages, the desire for peaceful coexistence of responsible citizens, who organise themselves and make decisions in public discourse together with municipal politicians, dominates today. Orientation along the common good, an open society, non-violence and tolerance have always belonged and still belong to the self-conception and intrinsic right of today’s civic society.

Gender Roles

After World War Two, a reactionary gender image was propagated. The stereotypical couple of the 1950s: a husband who only works for his family and a housewife who loves her children and supports him unconditionally.

In the late 1960s, a “new women’s movement” formed to counter restrictive gender attributions. Its representatives called for equality in all matters of private and public life by means of spectacular social and artistic interventions. Due to this pressure, women were given legal independence and more political influence.

The spirit of optimism encouraged activists of any gender and sexual orientation: they successfully fought for anti-discrimination laws. The mandatory equality of the genders and irrelevance of one’s sexual orientation as stipulated in constitutional law and the human rights was implemented with same sex marriage in 2019.

Diversity

The 20th century was defined by mass migration movements. During and after World War II, the greatest migration movements of the modern age took place under the regimes of violence and territorial and social dislocation. Many of the persecuted or stateless people sought refuge in Graz. The immigration of foreign workers, especially from Spain, Turkey and former Yugoslavia, also boosted economic growth in the post-war decades.

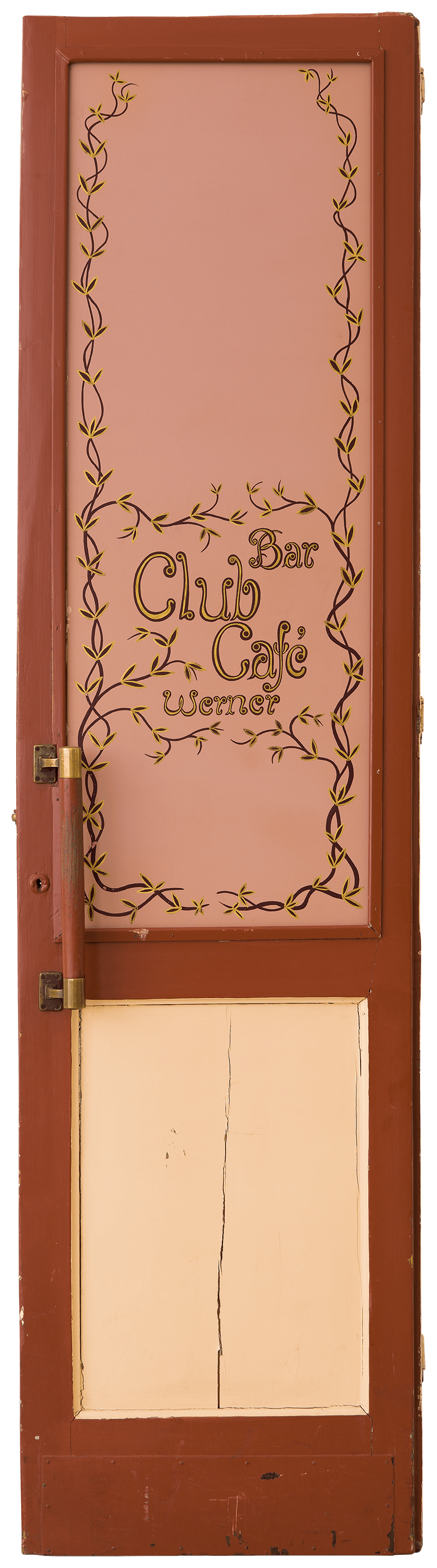

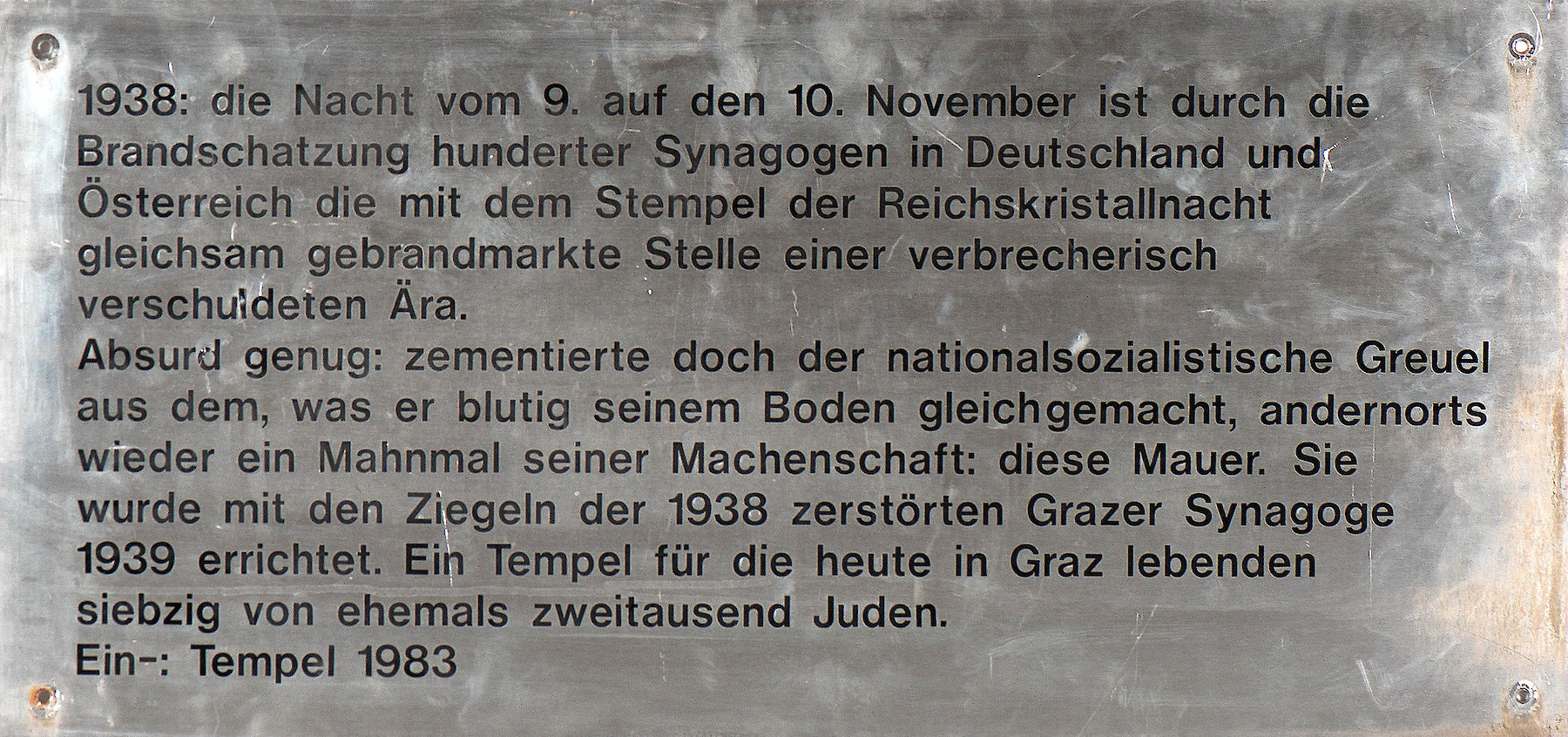

From the 1980s onwards, Austria was increasingly confronted with its repressed responsibility during the Nazi regime, not least in the wake of the Waldheim affair. The rebuilding of the synagogue in Graz, which was initiated in 1983, awakened the memory of National Socialist pogroms, the expulsion and murder of the Jewish population. The “City of the Popular Uprising”, which has been City of Human Rights since 2001, has shown a particular tension between repression and public reappraisal down to the present day.

Images of the City

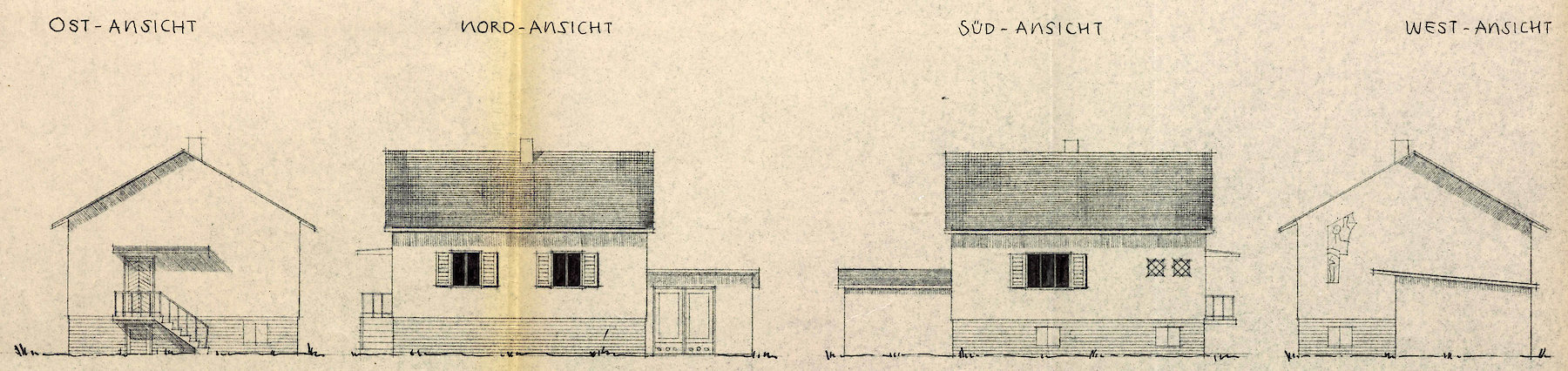

After the Second World War, Graz had to re-erect or build from scratch about half of all buildings. On the outskirts, makeshift settlements were part of the everyday cityscape. Little by little, the areas which belonged to the city since their incorporation in 1938 were randomly populated with one-family and two-family houses.

In the 1970s, general awareness matured both of the cultural value of the historical building stock and of the negative impact of too much car traffic on the quality of life. Parts of the city centre belong to the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage today and a pedestrian zone was built in the area of the city centre in 1972.

The issue of congestion, in particular the design of public transport, also to reduce particulate matter, still holds potential for discussion and action. In which form the city in a “humane” form is to be developed further is something Graz will still have to deal with in the future.

Elisabethhochhaus

People who live in the Elisabeth High-rise Building in boundless freedom enjoy an impressive vista of the old town. People who look at the high-rise building marvel at a peculiar “flaw” in the urban fabric. At a building height that had until then only been conceded to places of worship. While forest and grassland surfaces were used up for one-family houses in the peripheral districts, the Elisabeth High-rise Building provides an extreme vertical construction extension after all. It was planned in a time of major housing shortage and was built between 1964 and 1966—precisely at the time of the initiative “Rettet die Altstadt” (Save the Old Town).

Tiefgarage, Andreas-Hofer-Platz

The pale light of the light tower on Andreas-Hofer-Platz illuminates an infrastructure for motor traffic which filled a gap site in 1966. Until 1934, the Monastery of the Order of the Sisters of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel had been there, on Fischplatz, which had been dissolved by Joseph II and had become the “k.u.k. Monturdepot” (Imperial and Royal Uniform Depot). The underground car park, the pavilion of the rent-a-car, and the light tower tell of an era in which a lot was to be sacrificed to motorisation. Among other things, the bicycle demonstrations led by Erich Edegger and the establishment of “Alternative Liste Graz” responded to the “car-friendly city” around 1980.

Stadthalle Graz

Only sporadically used trade fair areas can rarely be found in the ‘shop window’ of a city. In 2003, the growing and economically aspiring Cultural Capital put a different emphasis on quality with the new Fair Hall. Already from afar, visitors coming from the south are welcomed with an inviting gesture by the bold flying roof, which has been conceived by the Graz-based architect Klaus Kada. With this masterpiece of construction engineering, which is supported by four pillars, Graz now had a representative hall for big events and thus also fired the starting pistol for an urban (sub-)centre between the Gründerzeit city and DIY stores and petrol stations.