Graz

1128–1600

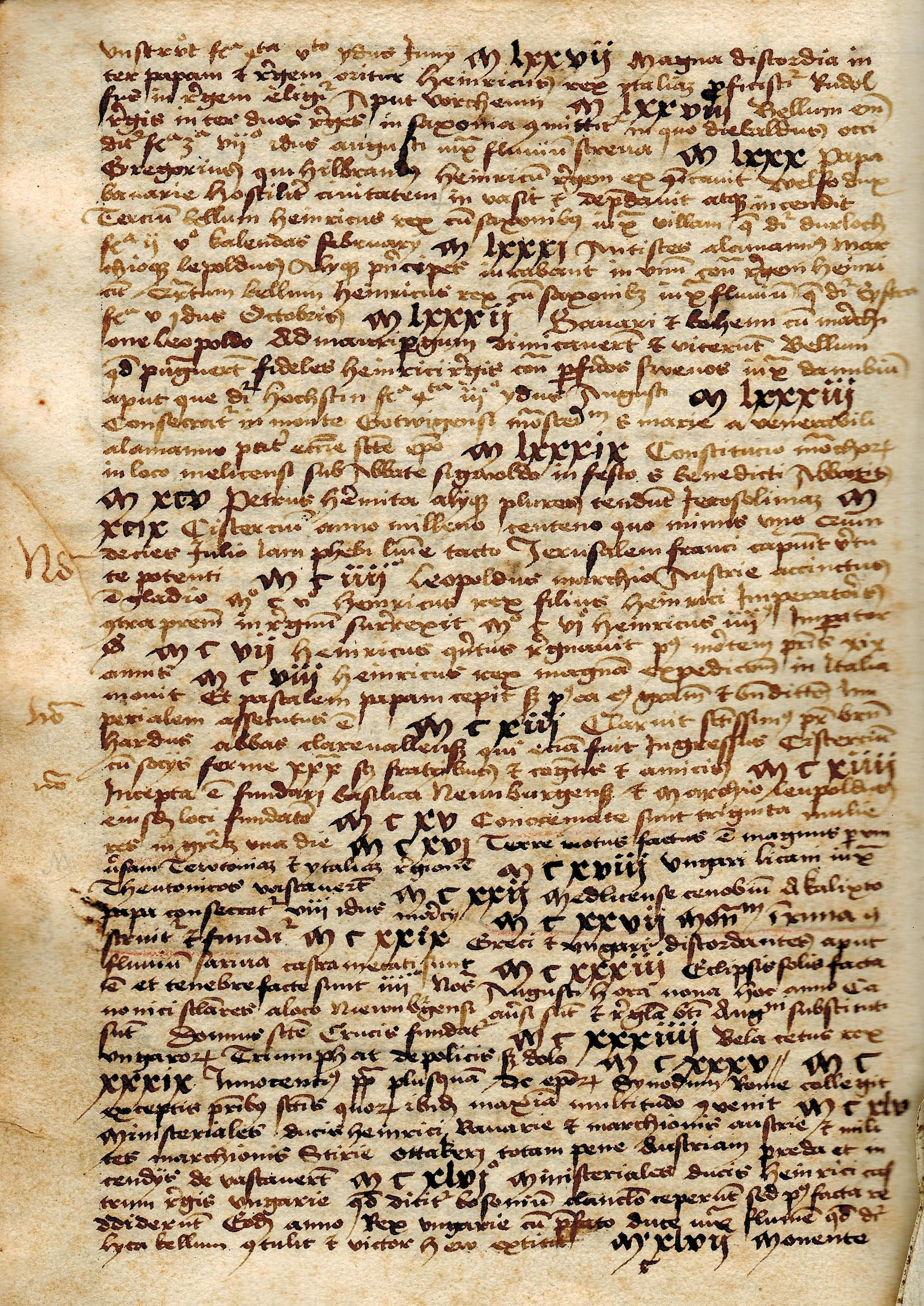

1128 as the year of the first documentary mention of the city of Graz is historically controversial, but not that it became a city in the 12th century with a market, jurisdiction and increasing fortification. For the regional rulers, the geographical location was becoming increasingly interesting for economic and strategic reasons. Graz became the seat of the Duchy of Styria and the Archduchy of Inner Austria. Parallel to this upgrade, a self-confident bourgeois class developed out of the tradesmen in the Middle Ages.

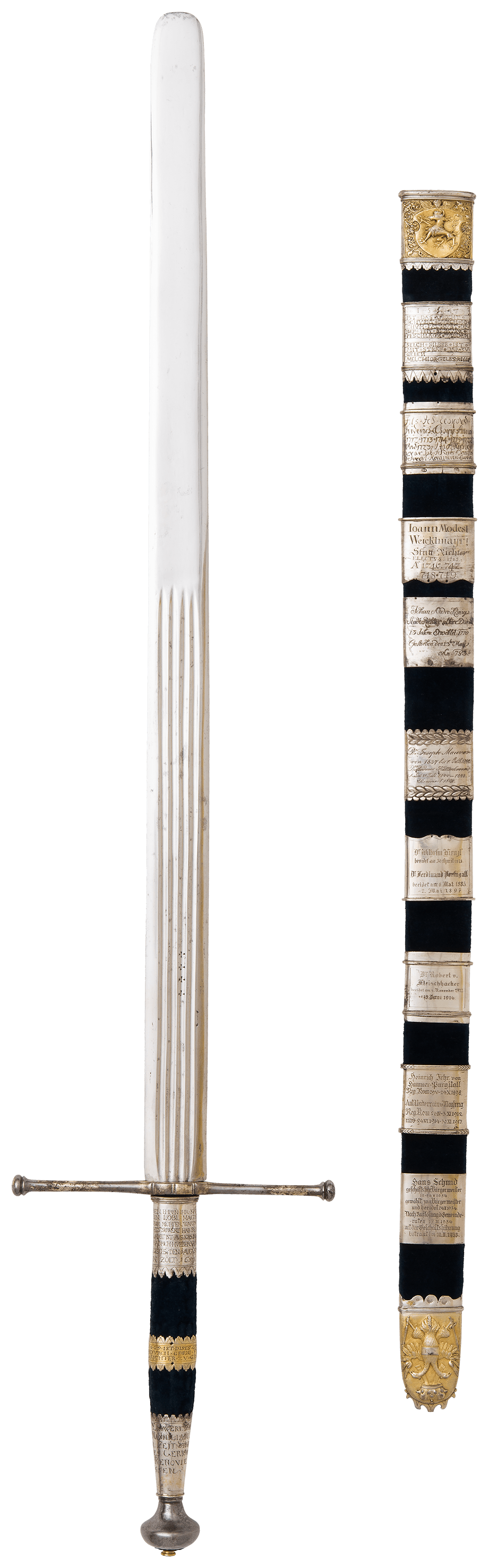

Flourishing times, wars and economic crises characterised the growing city—as did the way in which religious diversity was dealt with, which alternated between tolerance and pitilessness. The Jews were expelled at the insistence of the bourgeoisie in the late 15th century. The citizens, who were largely Protestants around 1550, were forced to become Catholics by the Catholic rulers by 1600 at the latest. Graz became the centre of the Counter-Reformation.

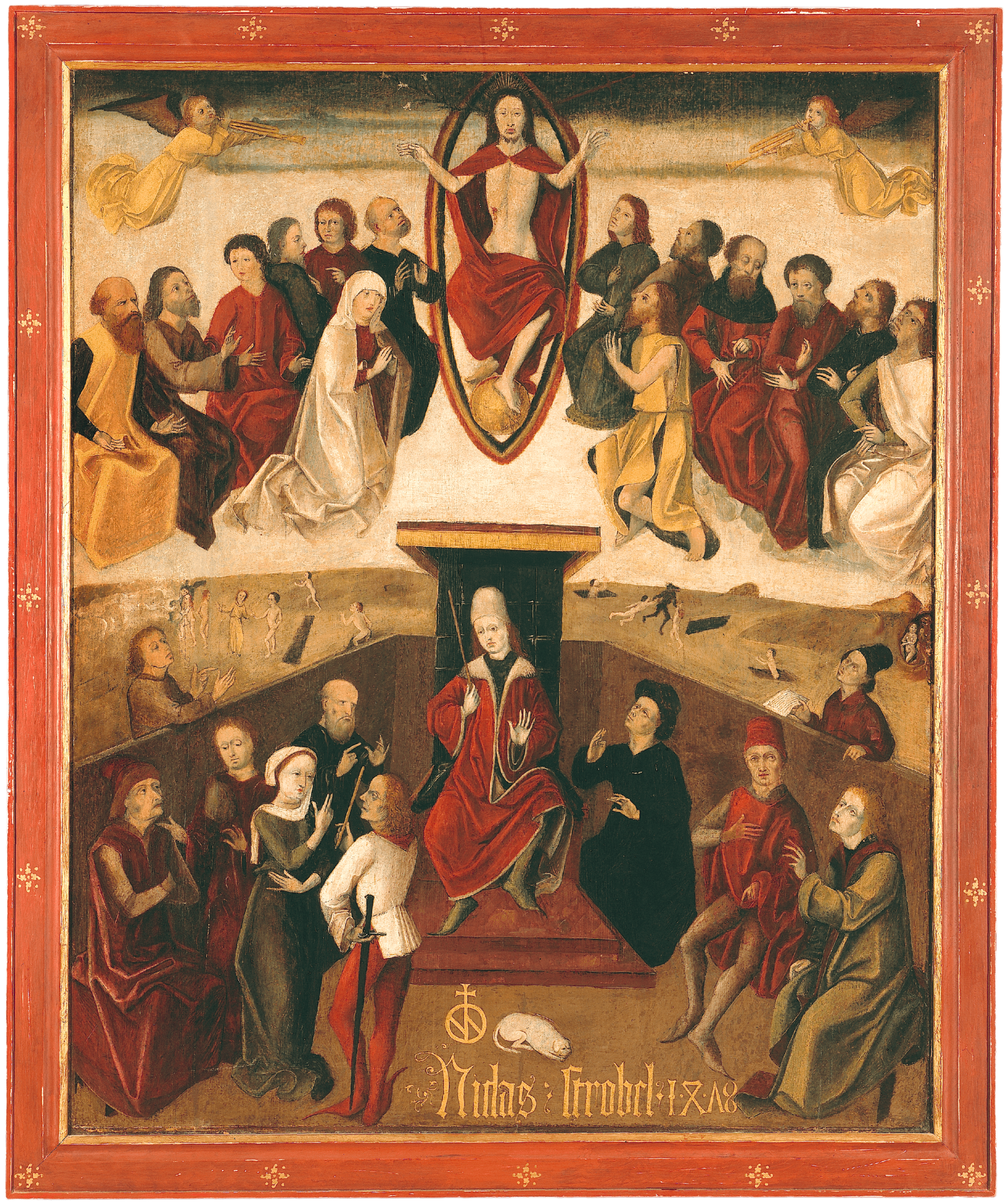

A court usher with stick and sword is putting a witness on oath. At that time, women were not allowed to stand before the court on their own account and had to be accompanied by a man.

City Judge Strobel, who can be recognised by his official attire and the judge’s stick, shows up in the centre of the image. He is the symbolic figure of self-confident civic jurisdiction. Two lay judges (jurymen) are sitting next to him.

City Judge Niclas Strobel was a master butcher by trade—which can be seen in the guild symbol. His wealth allowed him to hold the fixed-term offices of the city judge and the mayor several times.

The dog resting in front of the City Judge stands for the biblical figure of King Solomon. The “Solomonic judgment”, which is named after him, refers to a particularly wise and fair judgment.

The parties to the dispute and/or their representatives are standing outside the “Schranne”, a legally protected area separated by a wooden wall. The document, maybe a contract, may hint at a dowry dispute.

The Legal Autonomy of the City

The panel painting, dated 1478, has two narrative levels. On the one hand, it presents the city judge of Graz, Niclas Strobel, in the exercise of his office. It shows the court usher taking the oath of a (female) witness and the jury discussing the verdict to be decided. This makes it one of the oldest visual documents of municipal legal autonomy in Europe. On the other hand, the representation illustrates the religious world view of the Middle Ages. A heavenly scene of judgment takes place over the worldly one, because in the end all men have to answer to God.

The Battle of Confessions is at a Standstill

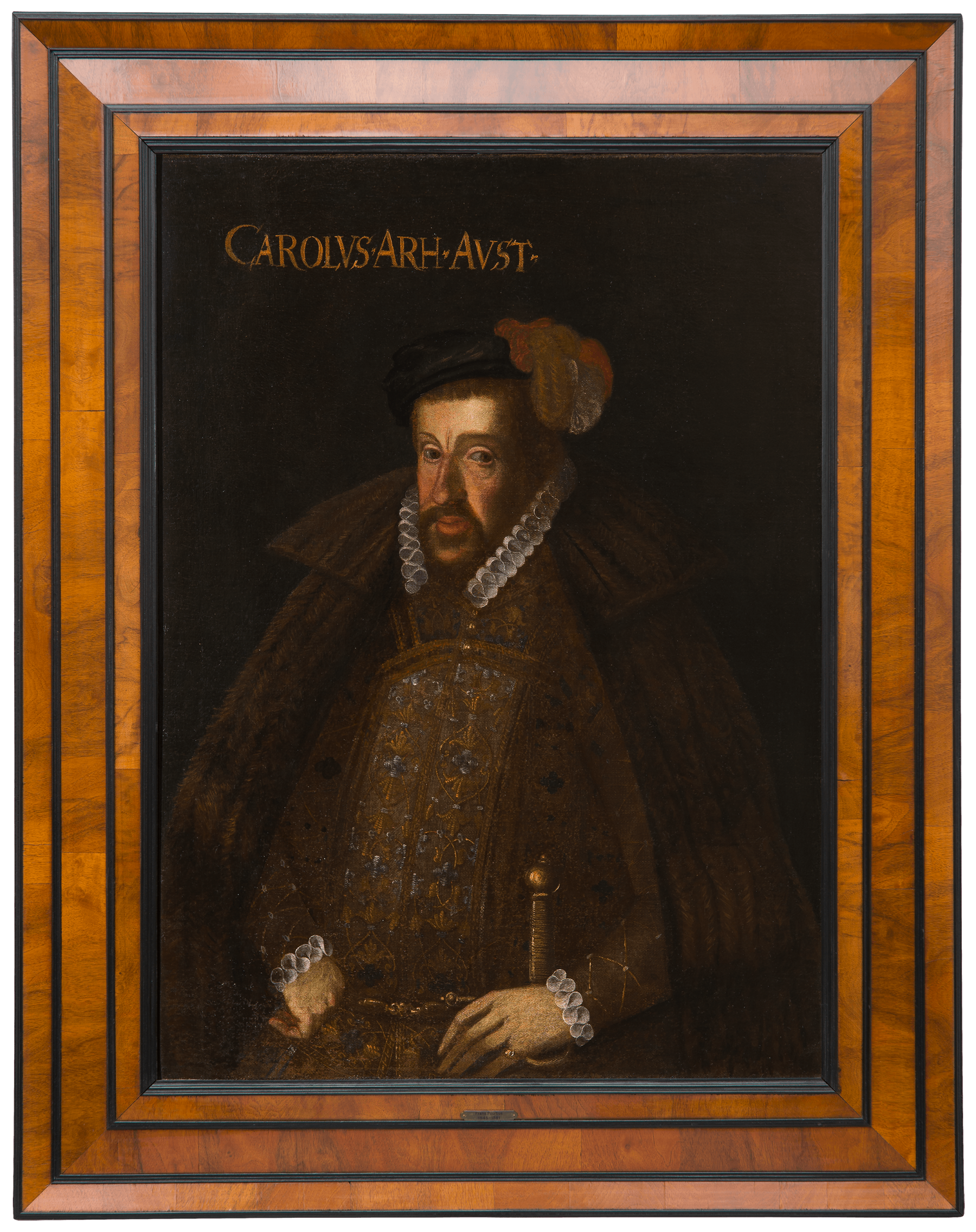

Monarchical mourning ceremonies served as propaganda for the rulers. A funeral procession was determined by the protocol of the court ceremony and reflected social conditions. When the corpse of Archduke Charles II of Inner Austria was taken from Graz to the mausoleum in Seckau in 1590, however, the real conditions appeared in a mild light. Despite the hard steps taken by Catholics during the Counter-Reformation, Protestants also paid their last respects to the dead monarch. As a framing bracket of the Empire, he was more important than the split denominational convictions of the participants at this very moment.

Graz as a Centre of Counter-Reformation

The transition from the late Middle Ages to the early Modern Period manifested in the open outbreak of religious conflicts. These were connected with the dynastic interests of the rulers. Abuse of power and secularization of the Roman Catholic Church as well as alienation from pastoral obligations towards the common people were the main points of criticism of the Reformation, which spread rapidly. In addition, there was the growing threat of the advancing Ottoman Empire in the East. After the victory over Hungary, the Ottomans tried to extend their sphere of influence to Vienna and the Austrian Hereditary Lands.

The Catholic powers under the leadership of the Hapsburgs did not want to accept either. The Ottomans were to be kept in check by the specially founded “military border” and the hereditary lands were to be violently recatholized. Graz, the capital of Inner Austria, became a centre of the Counter-Reformation—and the dawning of the 17th century became the age of religious wars.

Catholic Universities |

|

Nunciatures (diplomatic representations of the Apostolic See) |

|

Jesuit Colleges |

|

Borders of the Ottoman Empire in 1580 |

|

Borders of the Holy Roman Empire in 1580 |

|

Main areas of Counter-Reformation |

|

Areas dominated by Catholics |

|

Areas dominated by Protestants |

The Project of the City

Cities are among the achievements of the Middle Ages. Their economic power gradually outstripped that of the manors and represented a consistent source of income for territorial rulers and kings. Increasing self-confidence and striving for freedom manifested themselves in the demand for political autonomy and privileges. The social hierarchy of the Middle Ages broke up, and alongside the nobility, the clergy and the rural population, a new class emerged: the bourgeoisie. Diverse social groups and cultures formed the conurbation of the city. However, economic, social and political tensions were also unleashed there in acts of violence and revolts.

Graz first appeared as a city in the middle of the 12th century. From a city with free market rights, it quickly developed into the leading city of Styria and finally, as a result of the divisions of the estates of the Austrian hereditary lands, into the royal capital of Inner Austria.

Gender Roles

In the Middle Ages and in the early Modern Age, the relations between the sexes were determined by the order of the estates and the Catholic Church’s view of the world. Although a basic inequality between the “strong” man and the “weak” woman was assumed, the social status was considered first. Aristocratic women enjoyed privileges with respect to peasant or bourgeois men and influenced political events. “Unfit for military service”, bourgeois women were under guardianship and excluded from political participation.

The idea of female and male virtues was strongly influenced by religion. Women were supposed to fulfil themselves in the ideal of the mother (of God) and piety. Catholic saints served as role models for men and women in defending faith and the Church.

Diversity

In the Middle Ages, faith and piety structured everyday life—controlled and governed by power-political interests. The Catholic rulers fuelled conflicts between the different religious communities by means of prohibitions and privileges.

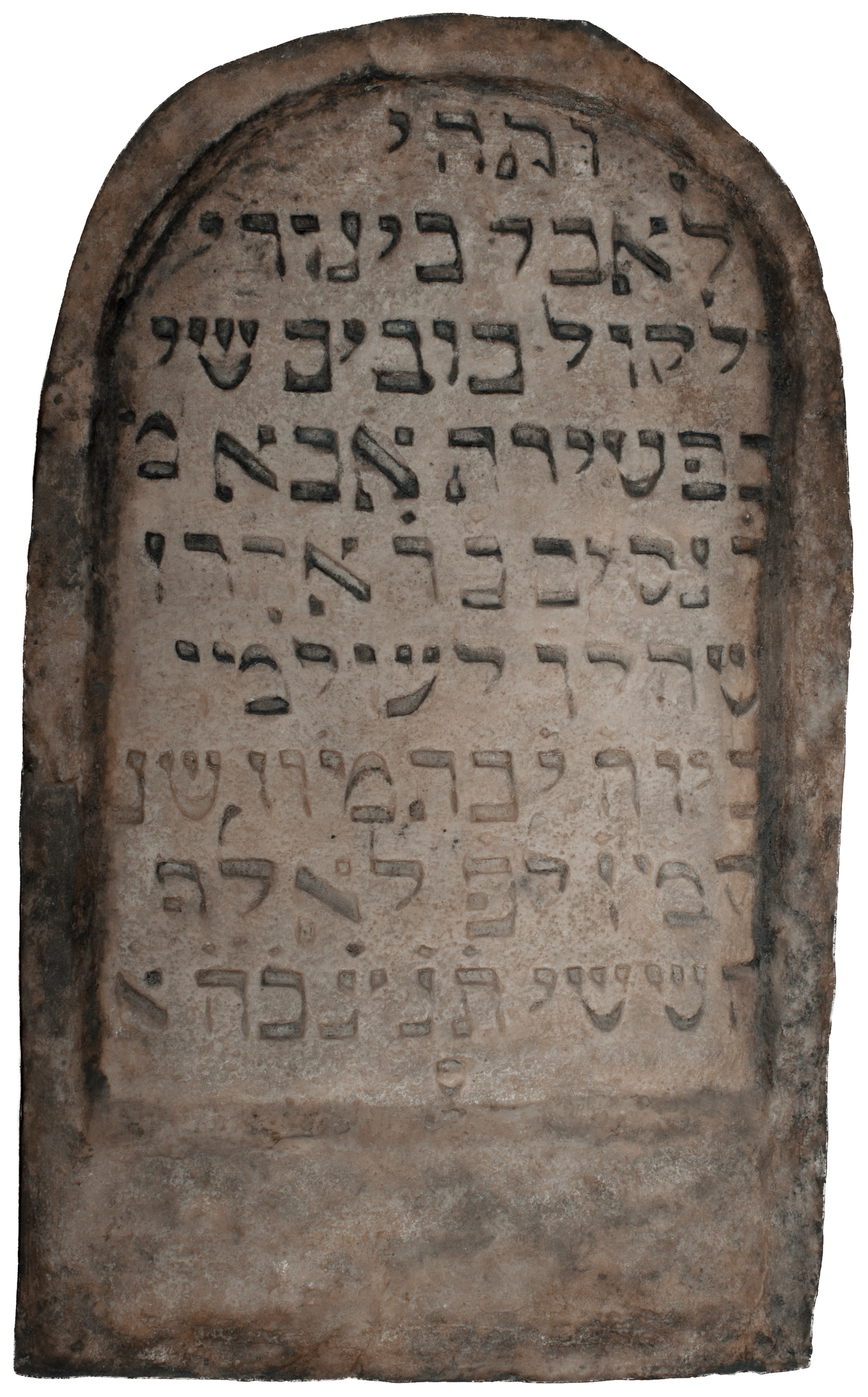

The Jewish population was sometimes forbidden to practice guild trade and agriculture, and the Christians were forbidden to do credit business—thus Jews primarily acted as lenders, merchants and pawnbrokers. They were protected when they paid their taxes; nevertheless, they were expelled twice in the 15th century: the Styrian estates, who owed them a lot of money, were needed as support in the war against the Ottoman Empire.

When the Protestants were needed in the war against the Ottomans, they were granted religious freedom. However, Ferdinand II revoked this. Many Protestant citizens left Graz as a result—among them Johannes Kepler.

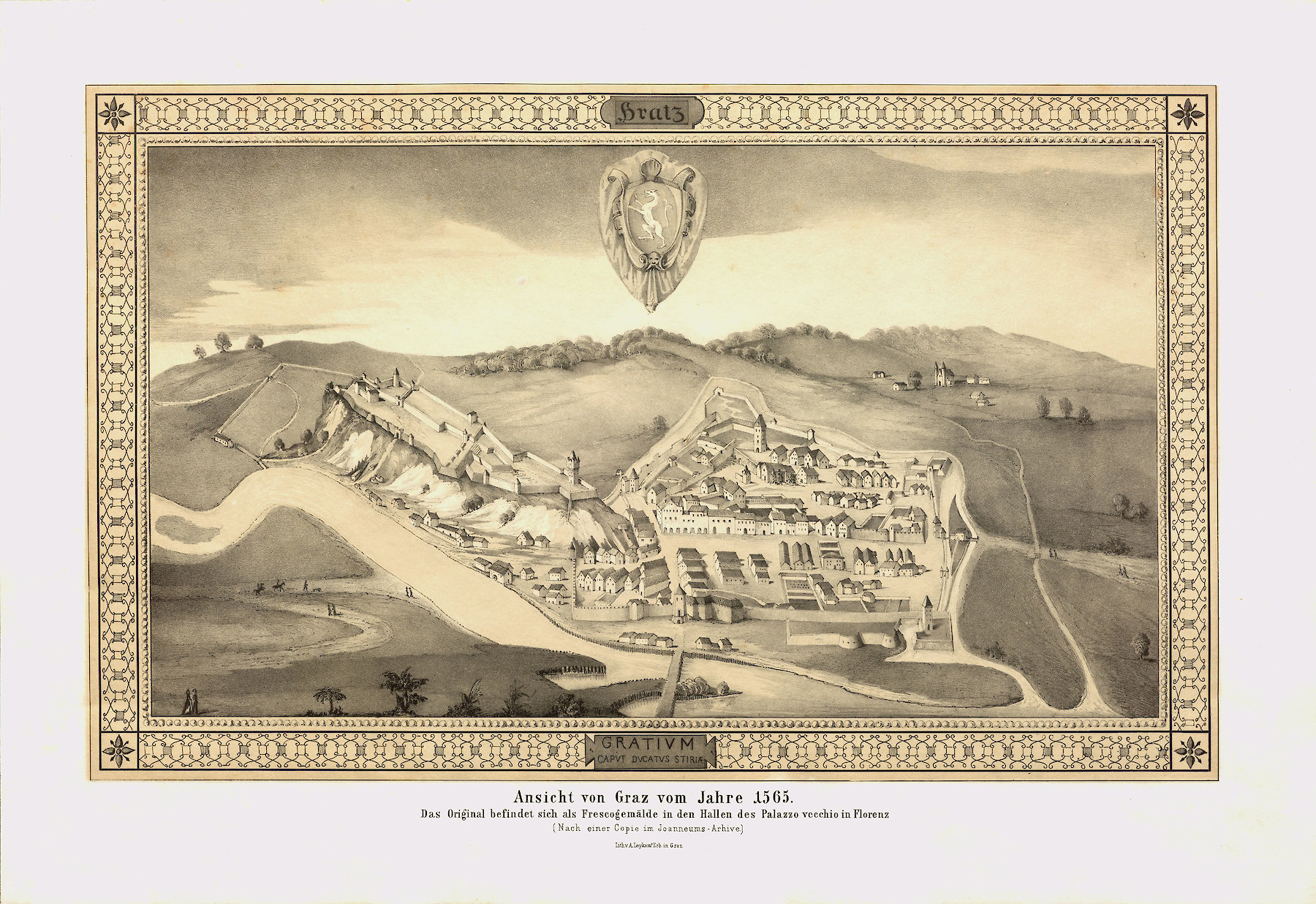

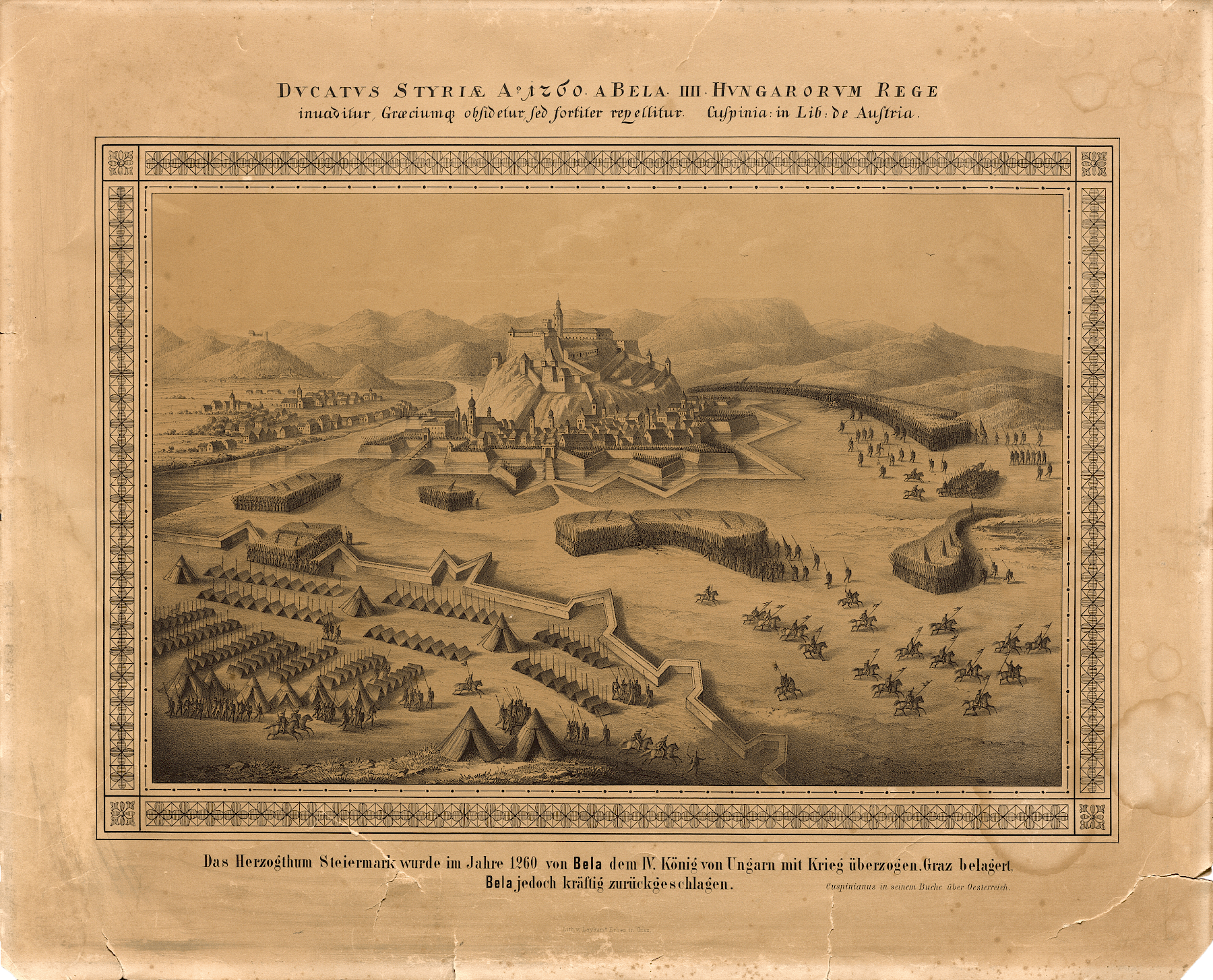

Images of the City

To this day, the tight and winding alleys and narrow elongated plots of land in the inner city point to the medieval layout of Graz. The small settlement around the Schlossberg developed into a town with a market, the Meierhof (a feudal estate), in the 12th century; as from the 13th century the market was walled in for the first time. The Schlossberg, on top of which there was already a fortress, constituted the centre. In early depictions, it is preferably depicted as a particularly imposing rock, not least to deter possible enemies.

From 1160 to 1438, the Jewish ghetto was located on the southern end of the market, with an own wall within the city wall. In the 13th century, the two settlements of the merchants and the Jews, which were separated by the market place, merged. The historical Murvorstadt on the right, western bank of the Mur River developed from a number of individual hamlets into an almost closed structure. It was not included in the fortifications for financial reasons.

Grazer Burg

“AEIOU“ was the both mysterious and proud monogram of this friend of humanists, alchemist, and collector of books of Saturnian character. This never deciphered sequence of vowels can be found on many works of art and buildings which were created or constructed under the reign of Frederick III. So, for example, in 1437, when Duke Frederick V of Styria was not yet head of the House of Habsburg and Roman-German emperor. Thus, the reading often heard in Austria, “Alles Erdreich ist Österreich untertan” (Austria rules the whole world), is not very probable.

Leechkirche

The Ottoman Wars were preceded by “armed expeditions to the grave (of Christ)” which were for the most part accompanied by disaster and political dispute. The Crusades combined pilgrimage and fight against the infidels with political and economical interests. One of their main supporters was the Teutonic Order, which was brought to Graz by Duke Frederick II in 1233. The Leechkirche of the Teutonic Order, the most signifi cant early Gothic sacral building of Graz, which was consecrated 50 years later, reminds of this.

Jesuitenkollegium

Serving absolutism, the Jesuits were—along with the Apostolic Nunciatures and the List of Prohibited Books—essential drivers of Counter-Reformation. Archduke Charles II brought these monastics specialized in preaching, schools and “guidance of souls” to Graz, which had meanwhile become a predominantly Protestant city, where they fi rst established a Catholic Latin school, and then the university. The massive complex of the Jesuit College reminds of this today, the nucleus of Graz University, which was founded in 1585.

Landhaus

The Catholic territorial prince aimed at absolute concentration of power. He was opposed by the predominantly Protestant Styrian estates who strove for political participation and freedom of religion. Their proud monument in Graz is the Landhaus, which was built by Domenico dell’Aglio in Renaissance style in 1565. But already in 1600, all Protestants, who had once represented the majority of the Graz population, were either ‘of right faith’ again or expelled from the city. Among them was Johannes Kepler, who served the Protestant estates.