The water from the Mur River was used for watering the fields, extinguishing fires, or—as can be seen here—for washing clothes. In the 19th century this was still heavy work, performed by women. The laundry was beaten with the hands, scrubbed, rinsed, wrung out, and hung over clotheslines in order to dry.

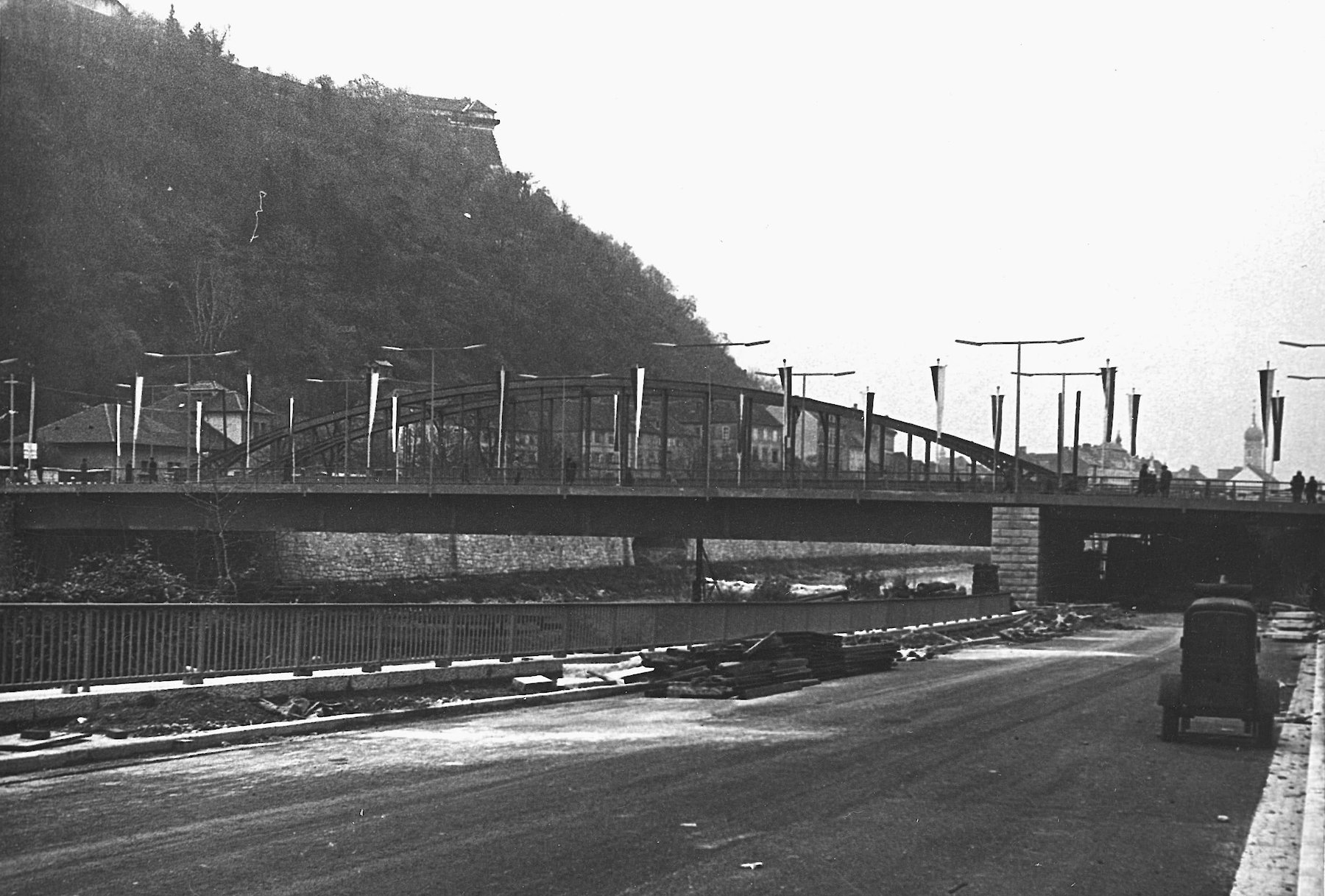

The chain bridge, which was named after Emperor Ferdinand I, was built by Franz Strohmeyer, the leaseholder of the “Überfuhr” (ferry) according to plans by the Vienna-based architect Johann Jäckl. It was the first chain bridge in Styria and the largest one in Austria. The Kepler Bridge stands at its place today.

The Rottal Mill with its two high gables, which belonged to the “Älteres Bäckerei-Consortium” (Older Bakery Consortium) is one of the enterprises that drew their energy from the left Mühlgang before the steam engine was introduced.

In the picture on the left there is a raft in the Mur River. In the early 19th century, the still unregulated river still serves as a transport route for people and goods.

The “Pruggmeier’sche Hadernstampfe” is a paper mill, i.e. a workshop where paper is produced of vegetable fibres and/or old rags. The paper produced this way was hung out to dry under the roof and in the garden.

Die neuerbaute Kettenbrücke der Hauptstadt Graz – Ansicht vom Schlossberg gegen Westen (The Newly Constructed Chain Bridge of the Capital of Graz—View from the Schlossberg to the West) Conrad Kreuzer, 1836

Early Industrialization—a Graz Idyll

In the foreground, the tranquillity of the Biedermeier dominates the scenery. The Mühlgang hosted the main energy source of the time: the water wheels of the mills. But what actually takes centre stage is the new industrial age. In 1833, the first Styrian and at the time biggest Austrian chain bridge, the Ferdinand Chain Bridge, was built on the location of today’s Kepler Bridge. In order to hold the roadway, two massive brick-built chain houses on both banks of the Mur River were needed. What we owe to technical masterpieces like this one is also the expansion of railway lines.

Tempera on paper

frame: 80 × 106 cm

Graz Museum / Photo: Edin Prnjavorac

The Artist Conrad Kreuzer

Conrad Kreuzer (1810–1861) was a landscape and veduta painter, draughtsman and portraitist. He was one of the most important representatives of the Styrian Biedermeier period and was the documentarist of the historical-topographical and early industrial Graz before the advent of urbanisation in the 19th century. In addition to tempera and oil paintings, the artist also created book illustrations (including illustrations for Gustav Schreiner, Grätz, 1843). He also worked as an art teacher. Kreuzer died of multiple sclerosis in the poorhouse and infirmary of Graz and was buried at the municipal Steinfeld cemetery.

Connecting the Banks of the Mur

In 1833, the Ferdinand Chain Bridge was built to connect Lendplatz with the left bank of the Mur. In 1880, the chain bridge was torn down again for safety reasons and an iron arch bridge was built in its place. Like the chain bridge almost fifty years before it, this bridge was at the highest level of technology at the time. What was special about it was its tied-arch (Langerscher Balken in German) as supporting structure. In the 1960s, the bridge could no longer cope with the large volume of traffic: The present-day Kepler Bridge was built.

The Mill Canals

The Mur was unsuitable for the operation of mills due to its irregular water level. Its large side arms, the left and right mill canal, served this purpose above all. The left mill canal, which is well recognisable in the painting, led from Weinzödl to Kepler Bridge. In order to gain free space for road and housing construction, it was filled in in the 1970s. The mill canal to the right, which is much longer with its 30 kilometres, still exists today. Grain mills, sawmills, textile and loden factories, paper mills, ironworks and finally electric power stations settled along the mill canals. Large enterprises, such as the Graz paper factory or Marienplatz square, where the Marienmühle was located, still point to the former function of these areas today.

Paper from the Mill

The cities and the demand for goods were growing with industrialisation. The administration alone, with its high paper consumption stimulated industrial mass production. What is also shown in this picture is a precursor: the “Pruggmeiersche Hadernstampfe”, a paper mill where paper was produced of vegetable fibres and/or old rags and was spread out to dry in large rooms under the roof and in the garden. The wood for paper production was partly supplied via the river until the 20th century.

The River as a Transport Route

Until the middle of the 19th century, the Mur served as the most important transport route. Salt, iron, wood and coal were transported downstream from the north, wine was transported upstream from the south by towing, i.e. with the help of horsepower and human power. Shipping came to a standstill towards the end of the 17th century, not least due to the extensive maintenance of these “towpaths”. Raft and flat-bottomed boat traffic was intensively continued until the 19th century. In the 19th century, freight traffic shifted increasingly from waterways to roads and railways due to the improved road and, in particular, rail network. As the last area, timber transport remained on water. After the First World War, this business also became unattractive due to the construction of hydropower plants.

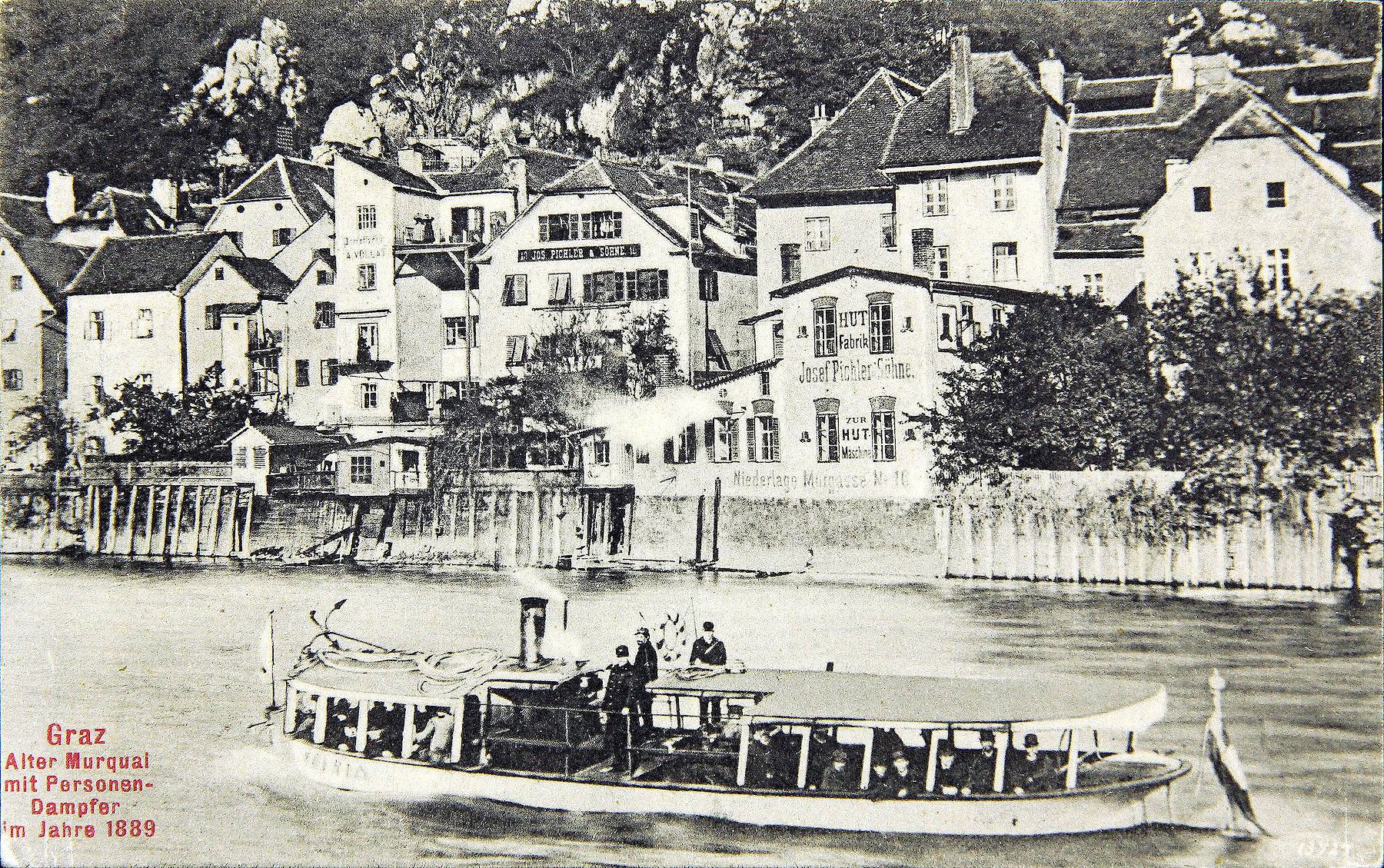

Passenger Transport on the Mur River

Not only goods, but also people were transported on the Mur. For example, raft trips were widespread towards the end of the 18th century. The river was hardly suitable for passenger ships, nevertheless some attempts were made. Steamships were used in the late 19th century. The Mur trips on the “Graz” and the “Styria” from 1888 onwards, however, had to be stopped soon due to too many incidents and even injuries.